Low winter water levels expose soils along Juanita Bay. Eagles like to roost in the cottonwoods.

Low winter water levels expose soils along Juanita Bay. Eagles like to

roost in the cottonwoods.

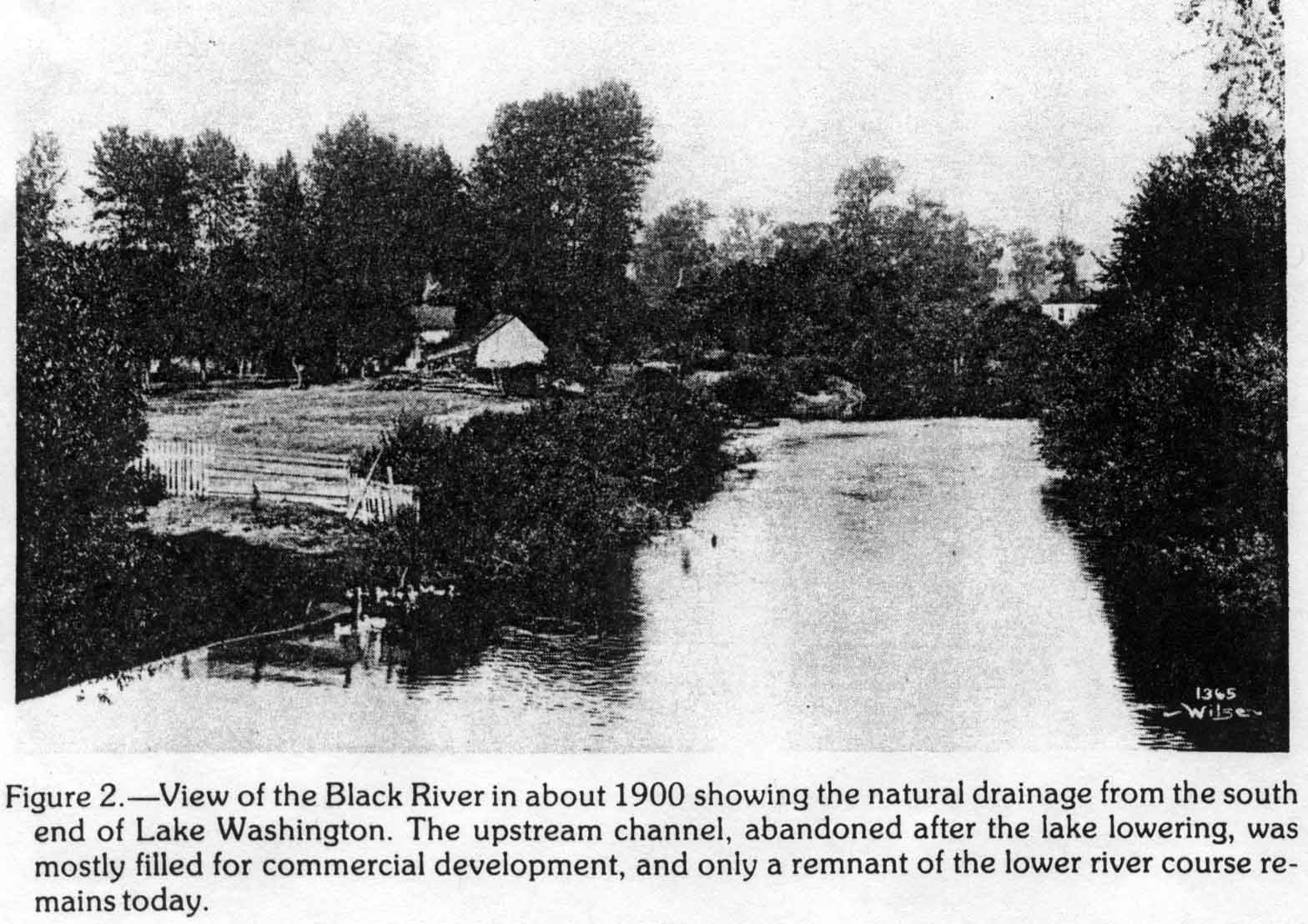

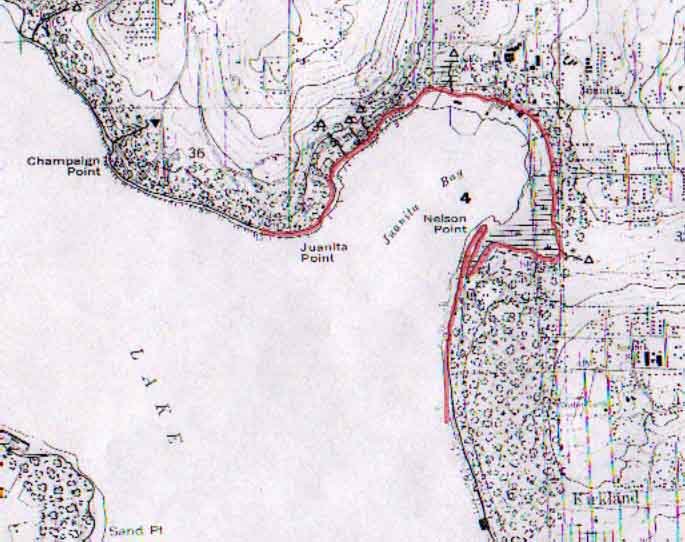

Original shoreline at Juanita Bay

Juanita Bay

was home to the Tabtabyook people who lived on the south shore of the bay

where the Indianola soils were exposed. The wetland areas provided them

with wapato and cattails for food and mats. Duck from the marshes along

the bay were another important food species, providing meat and eggs. The

white man came in the 1830's as fur traders bringing smallpox, which devastated

the local people. The settlers didn't arrive until about 1880. Logging

was the first activity in the area, and Juanita Creek was dammed for a

shingle mill. There was likely increased sedimentaion at this time, although

the salmon still spawned in the marshland around the bay. A bridge was

constructed across the Forbes Creek slough in the 1890's. In the early

1900's a dock was built in the bay for steam ferries which continued to

run until the lake was lowered. The less populated east side of Lake Washington

was a popular excursion site for Seattle residents. Duck hunters found

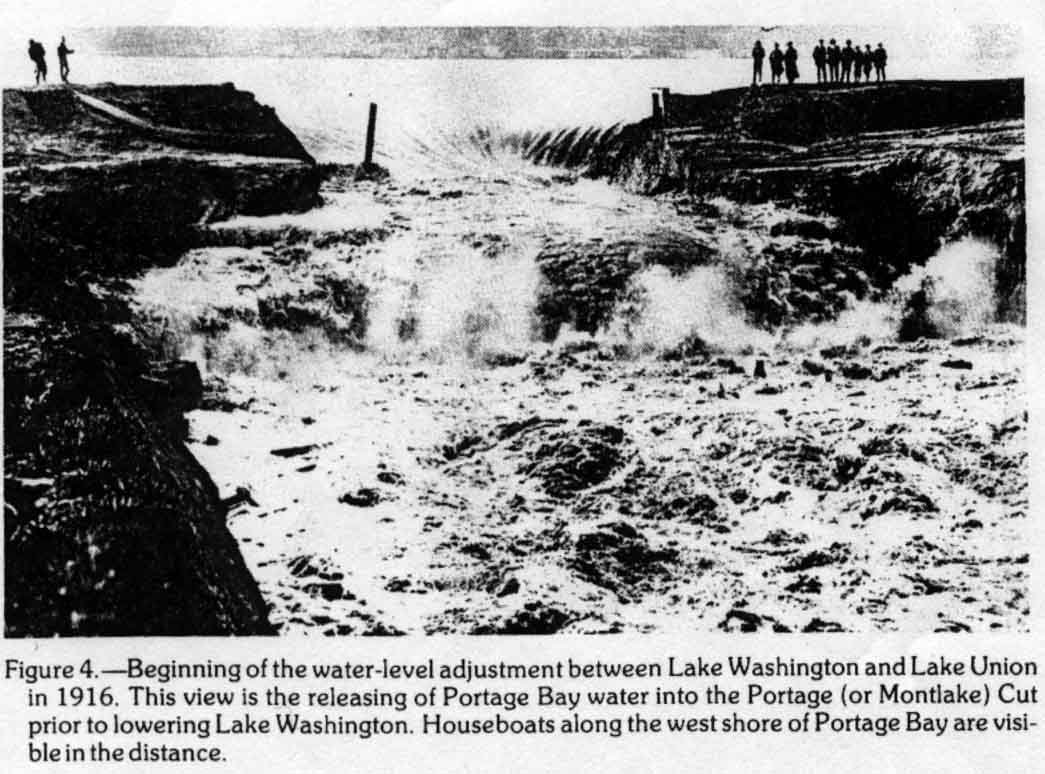

good luck here. In 1916, the bay became too shallow for the ferries after

the lake was lowered, and the salmon spawning was destroyed. 116 acres

were added to the area when the lake was lowered. A fill and bridge spanned the slough in 1932. A

golf course was constructed on the old Tabtabyook village site between 1927 and

1932, with fairways extending on fill over the saturated soils exposed in

1916. The area experienced increasing urbanization over the next decades.

In 1975 the golf course closed and the area was acquired by the City of

Kirkland as a park in 1984. Over the coming years the park was developed

with the help of Federal and State money, and especially the Washington

DNR Aquatic Lands Enhancement Account. The direction of the park was to

enhance and maintain a Natural area for the benefit and enjoyment of residents

and visitors. Currently the East Lake Washington Audubon Society among

others are planting native plants to further enhance the area.

The vegetation

developing here is a combination of natives and non-natives. A cursory

glance of the area note some different general areas. There is the cattail

dominated shoreline, a native emergent area. There is a large area dominated

by canary grass, a non native on seasonally saturated soils. There is the

willow, spirea, cornus shrub area, and an alder-cottonwood-willow wooded

wetland. These areas are designated by the water levels in the soils being

progressively lower. The cottonwoods are highly successful invaders of

the area where the soils have a slight elevation. Juanita Bay can be generally

regarded as a native dominated area, although the canary grass and blackberries

completely dominate large areas. The only vegetation management activites

have been cutting blackberries and planting native trees and shrubs to favor

birds.

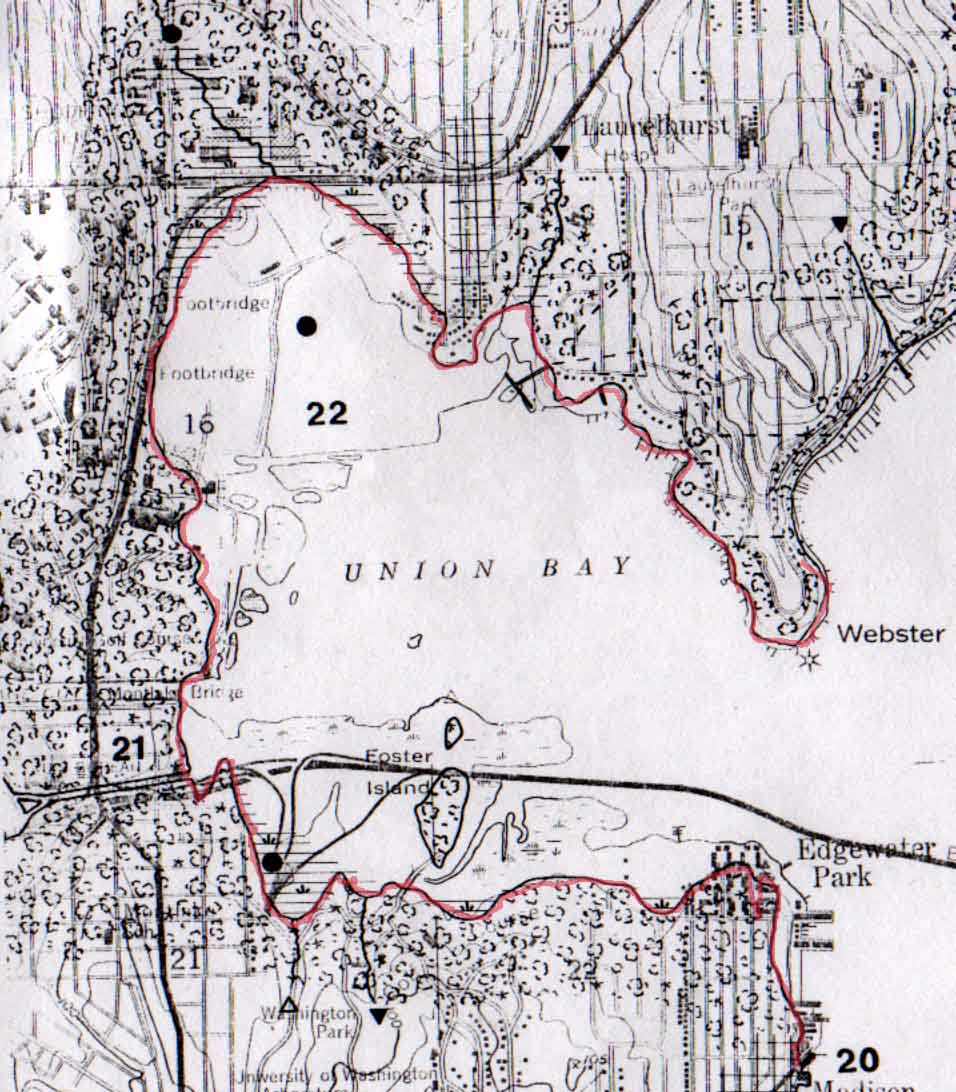

Original shoreline at Union Bay

Union Bay is an example of the radical changes people

in the Seattle area made to their environment. Originally the outlet of

Ravenna Creek and Green Lake, this was changed when Ravenna creek was diverted

to the West Point Treatment facility at Discovery Park, cutting off any

alluvial sedimentation. The University of Washington moved to the area

in 1913. When the lake was lowered these exposed soils became a marshy

area that was was beginning to acquire a shrubby wetland vegetation. Around

1926, Union Bay was loaned by the UW to the city of Seattle to be used

as a land fill for city garbage disposal. A 1959 plan for the area still

extolls how the Univerity was acquiring potentially valuable land so cheaply.

As the "swamp" was filled, it was covered with topsoil from various sources,

and converted to parking areas, housing and athletic fields. The

piling of refuse and soil raised the area up to 30 feet above the level

of the lake. When the landfill was closed in 1965, the remainder was covered

with inported soils, graded, and in 1971 planted with pasture grasses.

By now the UW had discovered that the unstable nature of the underlying

peat and the dramatic settling restricted many uses of the area. In 1974

it was proposed that the remaining undeveloped area be utilized as an arboretum,

and steps began in that direction. The Landscape architecture firm of Jones

and Jones developed a plan for the area in 1976. Because the refuse and

topsoil continues to compress the underlying peat layer, it is estimated

that the lake will eventually reclaim 30 acres of the 166 acre landfilled

area. In 1989 the EPA designated the area as a C1 hazardous waste area,

which meant that hazardous wastes were comfirmed to have been disposed

of at this site. In the 1990's the site was designated as the Union Bay

Natural Area, with a progressing set of goals. In 1992 Pentac Environmental

designated wetland areas. The plan will allow these wetlands to develop

as subsidence continues. The plan calls for keeping the pasture grass areas

open, and trying to convert it to a native shrub-steppe area. The plan

will have scattered native woodlands, but restrict their location to some

higher elevation, around the wetlands and in the Unmanaged Wildlife Area.

Roads will hopefully be eliminated, and trails maintained.

Peat islands going native (plus loosestrife!) outside the managed area

Restoration ecology students and hikers An eagle roosts in a dead cottonwood

The present use of the site is for university research and recreation. Hikers, joggers and bikers use the trails and can view wildlife such as many duck species, herons, eagles and beavers to name a few. The pasture grass areas are kept mowed, giving a park-like setting. The natural plantings have yet to make a visual impact. There is a desire to keep the area open and park-like which may interfere with the desire for a natural setting.

The future

should bring a slow development of native species to the area as restoration

continues, but most likely it will be a managed natural area. The settling

of the land into the lake will dictate a more wetland environment. This

will probably neccessitate the building of elevated walkways. Reconnection

of Ravenna Creek though not yet possible would make a great input toward

a more natural setting.

Plants will try to grow almost anywhere they are given a little soil, some moisture and light. They will try to grow in any soil that they happen to be placed in. They don't have the luxury of moving on. There are soil factors that each plant species are adapted to. The relationship of a plant species and the soil are interwoven over time. Most soil series are mapped from vegetation types after a relation has been determined. Soils provide the habitat and needs for the vegetation, and the vegetation provides the habitat and needs for the wildlife. Wetland species are adapted to different soil moisture regimes. The level of the water is more important than the soil type. Water depth and the frequency of inundation are major factors in determining soil chemistry and thus the selection of species that will inhabit the area.

In nature

there is a native succession of plants that will develop the ecology of a disturbed

area. Any disturbed area will fill with species regardless of the hand

of humanity. What plants move into an area depends on how they are adapted

to the site, and whether there is a source for seed or vegetative dispersal.

Succession can take a long time and consist of a number of species, or

it can be short and dominated immediately by one species. Along the shore

of both Union Bay and Juanita bay, agressive natives like the cattail have

moved right in and dominated the site. Likewise with native spirea and

willow brush and cottonwood, willow, and alder tree species in the saturated

mineral soils. Natural succession seems faster in these saturated areas.

It is a different story on the raised soils of Union Bay. Succession in

these drier areas will be much slower. Succession also has a progressive

effect on development of soils. Generally on bare mineral soils with little

organic material such as was laid over the trash at Union Bay weedy tap-rooted

species would slowly bring nutrients to the surface and develop an A horizon

that would be suitable for the next succeeding species. Succession on the

imported soils of Union Bay was not allowed due to the "state of the art"

in the 70's when the quick solution of seeding pasture grasses effectively

stopped any natural succession.

At Juanita

and the wetter areas of Union Bay we see that nature seems to want to establish

a cottonwood-willow-alder dense woodland at the edges of the saturated

zone, with the shub willow dogwood spirea growing down to the edge of standing

water where the cattails dominate. We can see at Juanita that these natural

areas form a dense thicket are not amenable to human traverse, but are

very suitable for wildlife, as human activity is restricted. At Juanita,

this is remedied with elevated walkways. At Union Bay, there is a stated

desire to keep large areas open, which favors humans and geese but few

other species. Continued mowing restricts the natural succession of woody

species that want to move in.

Willows and cattails are natural invaders on the original organic soils outside the fill.

The comparison

of these two areas tells us that a natural hydrologic system providing

a somewhat stable drainage system has more effect on the soils and vegetation

in these natural areas than any other factor. The uneven settling of the

soils at Union Bay makes establishment of a permanent wetland gradation

from emergent to dryland almost impossible until the settling slows. The

continuing variation in elevations will cause confusion in the natural

succession of plants, and changes in the saturation and chemistry of the

soils. Even the strange imported soils of Union Bay would settle into some

natural gradation given time.

The comparison

shows us that the natural vegetation that will come into the native exposed

soils creates a habitat that is not traversible by humans except on walkways.

The desire

to keep the open areas in Union Bay native means that humans will have

to control the natural processes here, as nature will want to move in.

At Juanita, there were fewer man made issues to deal with, and they started

with a site that was already filled with a fairly natural succession of

native vegetation with a few weedy imports. The open space problem is solved

by leaving it out of the areas designated natural. Union Bay is an area

still looking for a natural stability, and the emphasis is on native species.

Juanita Bay has already reached some kind of accomodation with the human

presence, and the plants that have moved in, albeit not all native. In

our world where global distances are short, and species of plants as well

as races of humanity are mixing in all locations, "nature" may not

be restricted to what was indigenous, but to go with the flow with today's

mixed natural processes. A new natural diversity. Humanity is a part of

nature. Nature and humans together are looking for a balance between stability

and change, management and freedom, urban and natural, natives and

immigrants. These areas will always be managed to a certain extent.

Blackberries on the higher areas of the old inlet behind Nelson Point

The beaver dam and pond on Forbes creek

Pond formed by subsidence

Planted pasture grasses have dominated the site for 30 years

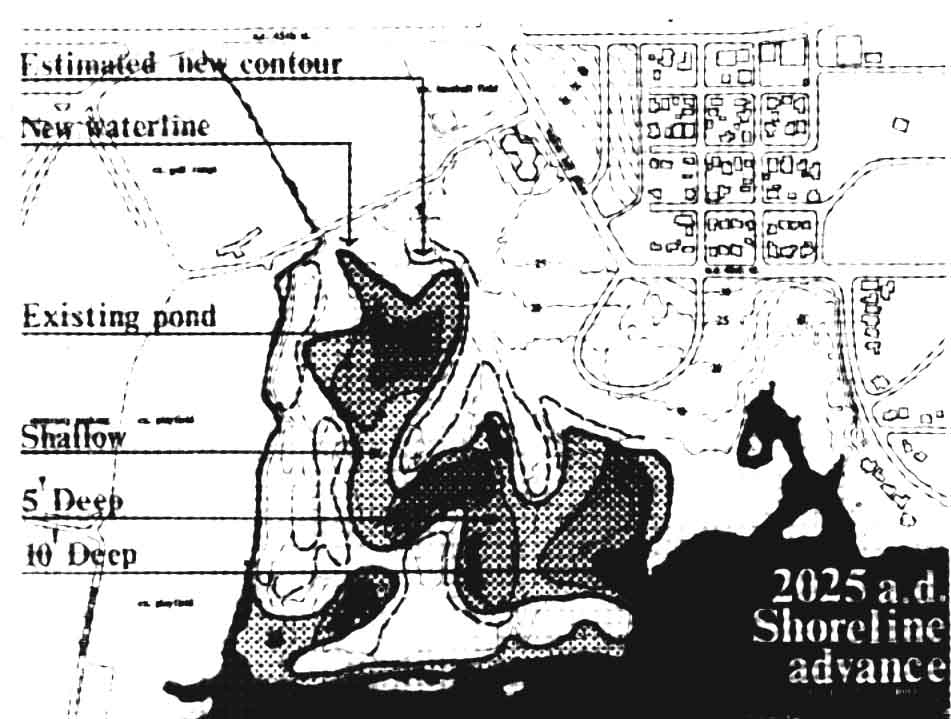

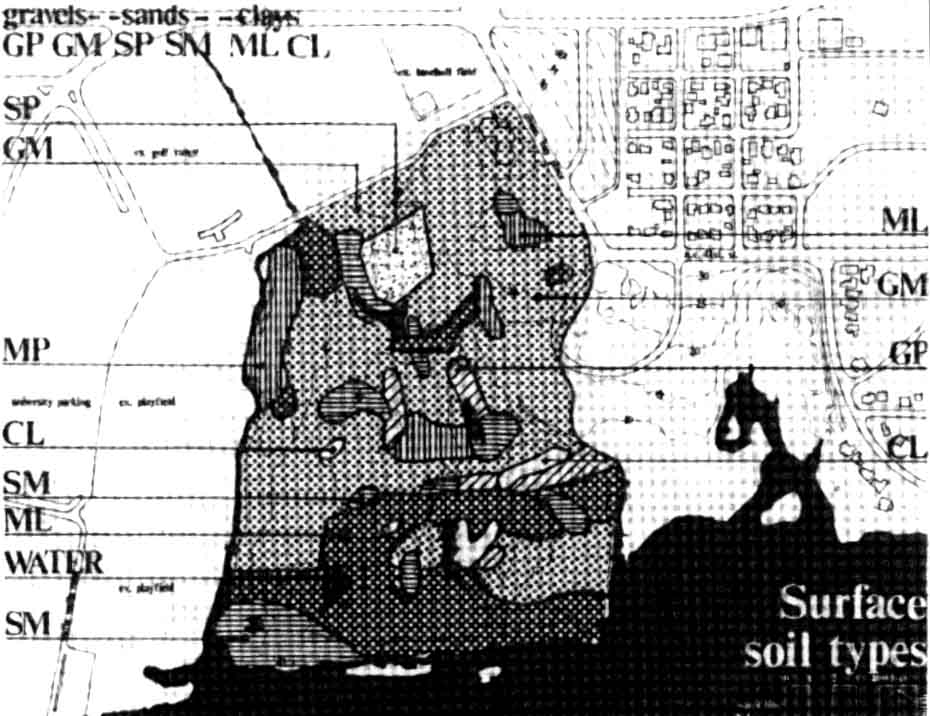

Projected Union Bay shoreline by Jones & Jones General soil types at Union Bay by Jones & Jones

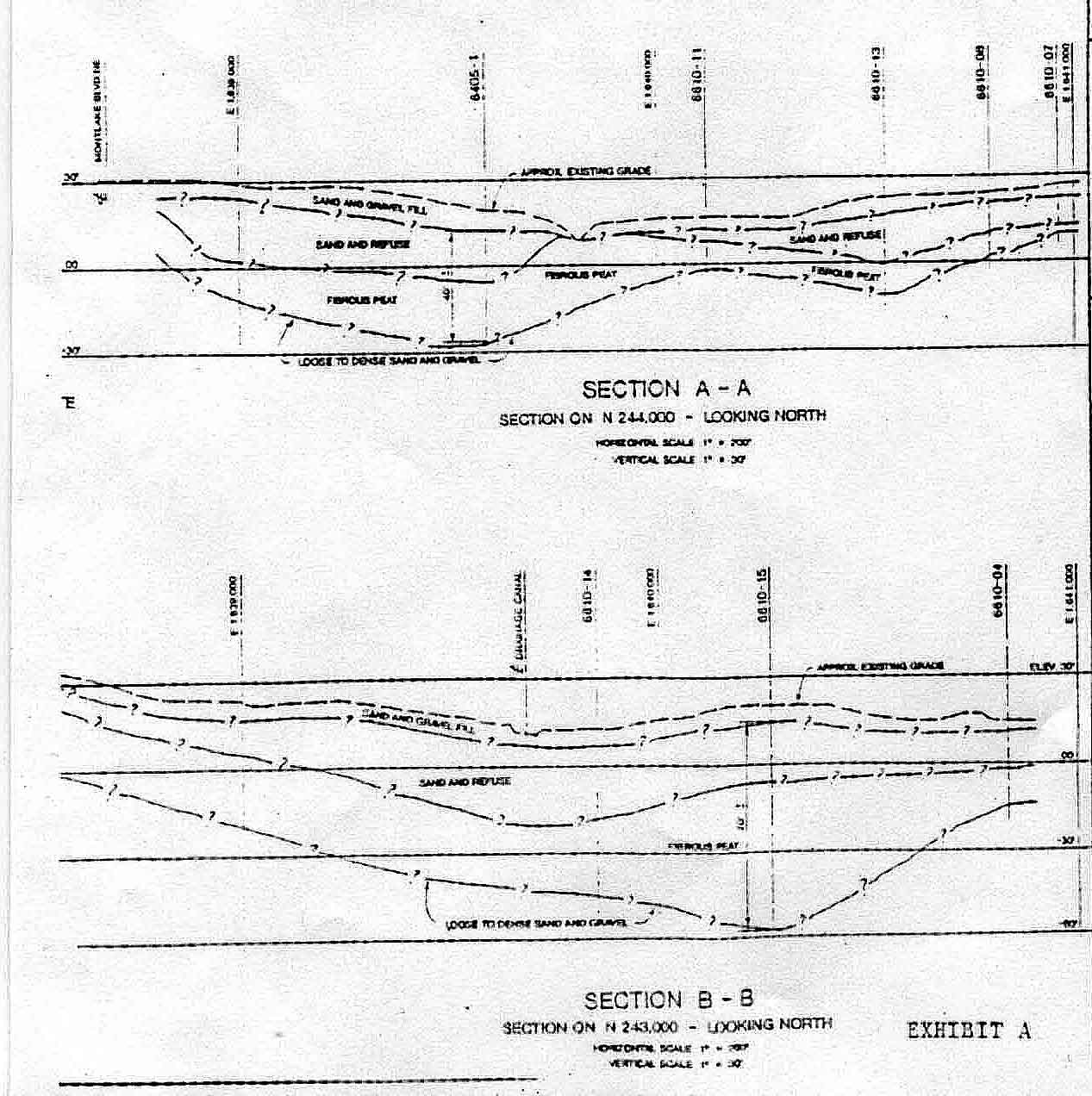

Cap layers at Union Bay

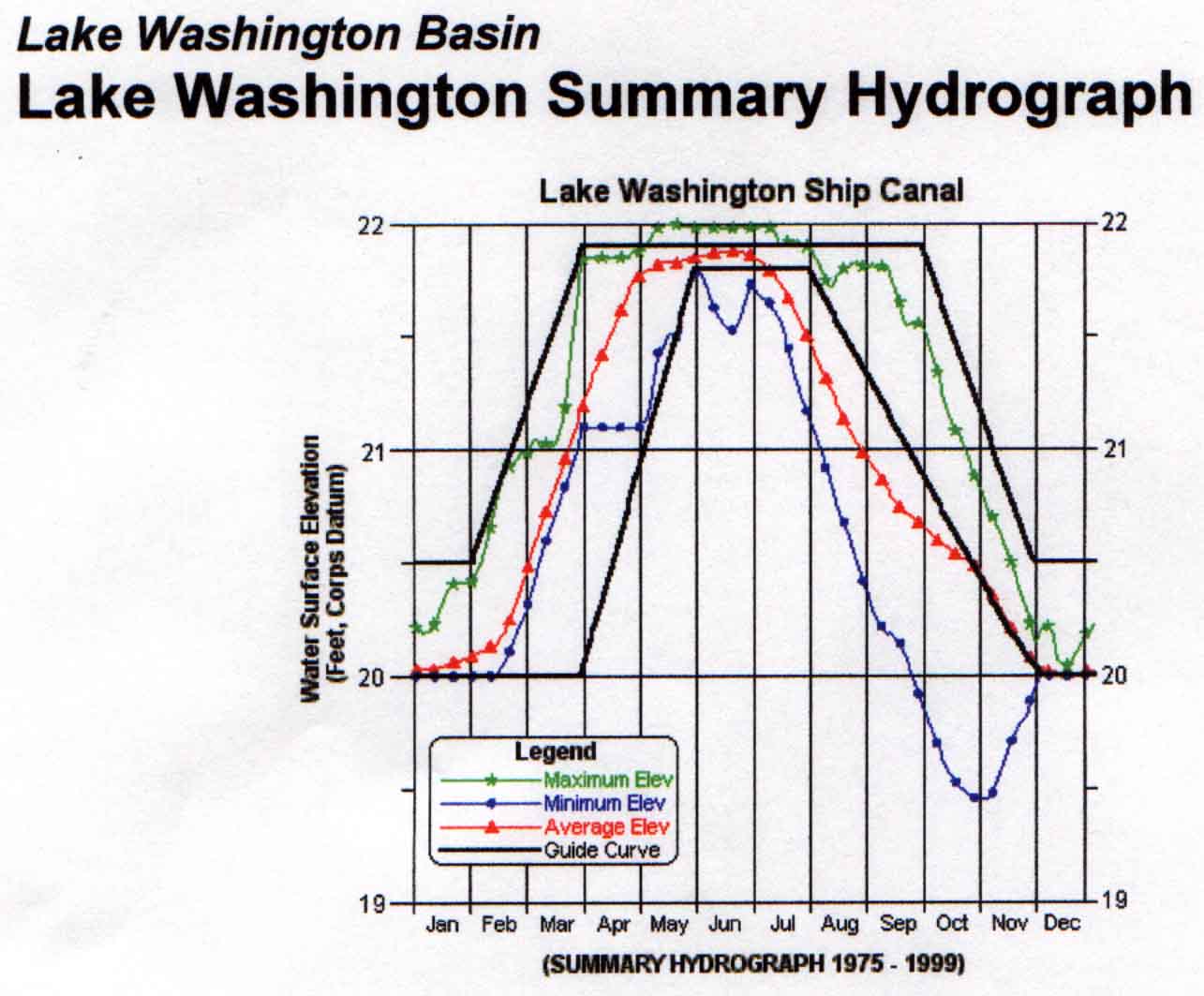

Seasonal Water level changes in Lake Washington

Teresa Sollitto, Parks Project Coordinator, Parks and Community Services Dept., City of Kirkland

Michael Chrzastowski, Historical Changes to Lake Washington and Route of the Lake Washington Ship Canal USGS

Jones & Jones, Landscape Architecture Report on Union Bay Natural Area 1976

Dean McManus, Postglacial Sediments in Union Bay, Northwest Science V. 37

Pentac Environmental Wetand Delineations Union Bay Natural Area 1992

Management Guidelines for Union Bay Natural Area UHF 572 Winter 1997

www.historylink.org

Report to the President and Provost, University of Washington,

Management Plan for the Union Bay Shoreline and Natural Areas 1995